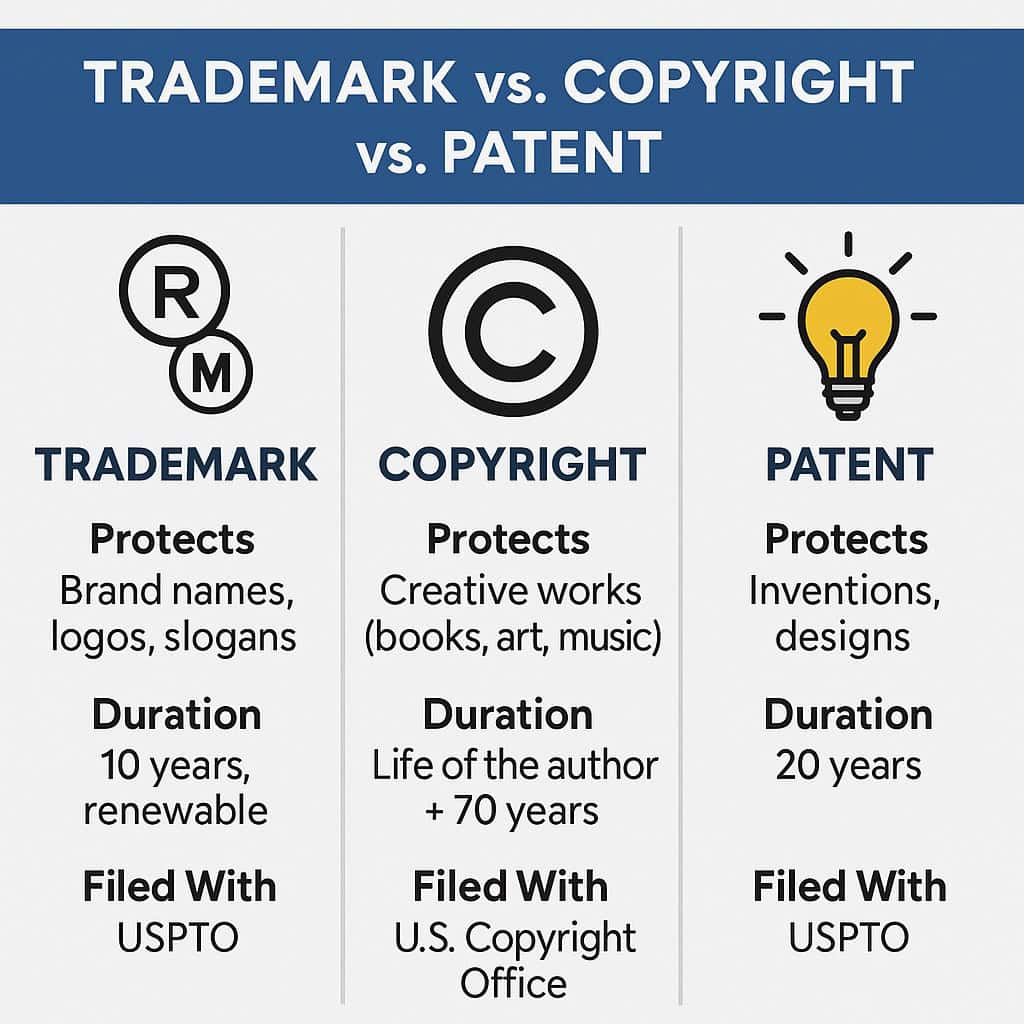

We often get the question from clients and potential clients what is the difference between trademark, copyright, and patent and what does each protect. When it comes to protecting your ideas, brand, or creative work, the terms trademark, copyright, and patent often get used interchangeably — but they are very different legal tools. Choosing the wrong one (or missing protection altogether) can cost your business thousands in lost revenue and even legal disputes if not done correctly.

So, this article will break down the differences, and explain when to use each.

What is a Trademark?

A trademark protects your brand identifier such as:

- Business names

- Product Names

- Logos

- Slogans

- Symbol

- Sounds and Colors

- Product Packaging (trade dress)

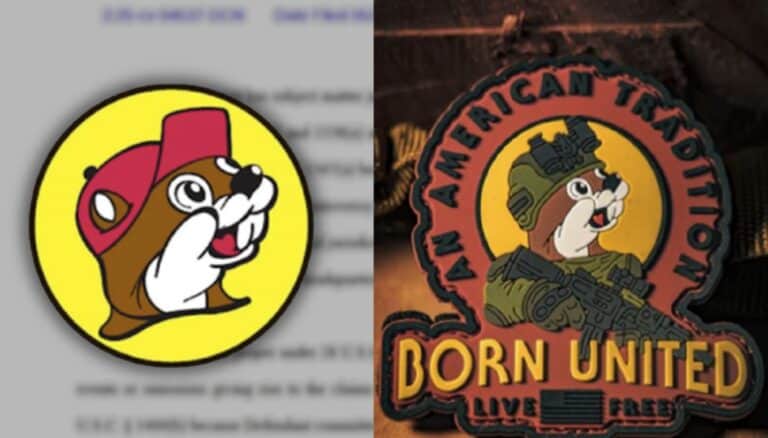

The primary purpose of trademark law is to help consumers make informed purchasing decisions. When you see a specific logo or brand name, you expect a certain level of quality and consistency based on your past experiences or the brand’s reputation. Trademarks prevent other companies from using similar marks that could mislead consumers into thinking they’re buying from you when they’re not. This protects consumers from being deceived and ensures fair competition in the marketplace.

For businesses, trademarks are invaluable assets that represent goodwill, reputation, and years of investment in building customer relationships. They allow you to:

- Establish brand recognition so customers can easily identify your products

- Build customer loyalty tied to your specific brand

- Create business value that can be licensed or sold

- Take legal action against infringers who try to capitalize on your reputation

Trademark rights generally arise through actual use in commerce, though registering your trademark with government authorities (like the USPTO in the United States) provides additional legal benefits, including nationwide protection, legal presumption of ownership, and the ability to use the ® symbol. The scope of protection depends on factors like how distinctive your mark is, your industry, and your geographic market.

To keep your trademark protection strong, you need to actively use it in commerce, enforce it against infringers, and avoid letting it become generic (like what happened to “aspirin” or “escalator”).

USPTO Resource: United States Patent and Trademark Office – Trademarks

What is a Copyright?

A copyright protects original creative works fixed in a tangible medium, such as:

-

Books, blogs, and articles

-

Artwork, photography, and designs

-

Music, movies, and software code

Copyright gives the creator the exclusive right to reproduce, distribute, perform, and display the work.

Copyright law protects original works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible form—meaning they exist in some concrete way that can be perceived, reproduced, or communicated. This includes literary works, visual arts, musical compositions and sound recordings, dramatic works and choreography, architectural designs, and even databases and compilations. The key requirement is originality: the work must be independently created and possess at least a minimal degree of creativity.

Copyright doesn’t protect ideas, concepts, procedures, methods, systems, processes, discoveries, or facts themselves—only the specific expression of those ideas. For example, you can’t copyright the idea for a murder mystery novel, but you can copyright your particular story with its specific characters, plot, and dialogue. Similarly, copyright doesn’t protect titles, names, short phrases, slogans (these may be trademarks), or works that lack sufficient creativity.

Copyright ownership grants creators several exclusive rights, often called a “bundle of rights”:

- Reproduction right: The ability to make copies of the work in any format

- Distribution right: Control over how copies are sold, rented, leased, or given away

- Derivative works right: The power to create adaptations, translations, or modifications (like turning a book into a movie)

- Public performance right: Control over performances in public spaces (particularly relevant for music, plays, and films)

- Public display right: The right to show the work publicly (important for visual arts)

- Digital transmission right: For sound recordings, the right to perform works via digital audio transmission

Unlike patents and trademarks, copyright protection is automatic. The moment you create an original work and fix it in tangible form—whether you write it down, save it to a computer, paint it on canvas, or record it—you own the copyright. You don’t need to register, publish, or place a copyright notice (©) on the work, though doing these things provides additional legal advantages.

Copyright Registration Benefits

While not required, registering your copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office (or equivalent authority in other countries) provides significant benefits:

- Creates a public record of your copyright claim

- Allows you to file infringement lawsuits in federal court

- Enables you to collect statutory damages and attorney’s fees in infringement cases

- Provides prima facie evidence of copyright validity if registered within five years of publication

Duration of Protection

Copyright doesn’t last forever. For works created after 1978, protection typically lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years. For works made for hire, anonymous works, or pseudonymous works, protection lasts 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter. After copyright expires, the work enters the public domain and can be freely used by anyone.

Fair Use and Limitations

Copyright isn’t absolute. The doctrine of “fair use” allows limited use of copyrighted material without permission for purposes such as criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. Courts consider four factors when evaluating fair use: the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount used, and the effect on the market value of the original work. Other limitations include library archiving, first sale doctrine (which allows you to resell a book you purchased), and specific educational exemptions.

International Protection

Thanks to international treaties like the Berne Convention, copyrighted works are protected in most countries worldwide. When you create a work in one member country, it’s automatically protected in all other member countries, though the specific rights and enforcement mechanisms may vary by jurisdiction.

Transfer and Licensing

Copyright can be transferred, sold, or licensed to others. Authors often license specific rights while retaining others—for example, granting a publisher the right to print and distribute a book while keeping film adaptation rights. These agreements should always be in writing and clearly specify which rights are being transferred and under what terms.

Copyright Recourse – copyright.gov

What is a Patent?

A patent protects inventions and processes that are new, useful, and non-obvious. There are three main types:

- Utility patents – Protect new processes, machines, or compositions of matter.

- Design patents – Protect the unique ornamental design of a product.

- Plant patents – Protect new varieties of plants that are asexually reproduced.

👉 Example: Apple’s design patent for the iPhone’s rounded corners helped it defend its iconic look in court.

What Patents Protect

Patents are the most powerful—and most complex—form of intellectual property protection. They grant inventors exclusive rights to prevent others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing their invention for a limited time. Unlike copyrights and trademarks, patents protect the underlying functionality and technical innovation itself, not just its expression or brand identity.

The Three Requirements for Patentability

To qualify for patent protection, an invention must meet three critical criteria:

1. Novelty (New): The invention must be genuinely new and not previously known or used by others. This means it cannot have been publicly disclosed anywhere in the world before the patent application is filed. Even the inventor’s own public disclosure can destroy novelty, which is why inventors must file patent applications before publishing papers, presenting at conferences, or offering products for sale.

2. Utility (Useful): The invention must have a specific, substantial, and credible use. It must work and provide some identifiable benefit. This is generally the easiest requirement to meet—most inventions that function at all satisfy the utility requirement.

3. Non-obviousness: This is often the most challenging requirement. The invention must not be an obvious improvement or combination to someone with ordinary skill in the relevant field. Even if something is new and useful, if experts in the field would consider it an obvious next step, it’s not patentable. Patent examiners assess whether the invention represents a genuine inventive leap beyond existing knowledge.

Types of Patents Explained

Utility Patents are the most common type, covering approximately 90% of all patents granted. They protect:

- Processes: Methods of doing something, like manufacturing techniques or business methods

- Machines: Devices with moving parts or functional components

- Articles of manufacture: Physical objects or products without moving parts

- Compositions of matter: Chemical compounds, mixtures, or new materials

- Improvements: Significant enhancements to existing inventions

Examples include pharmaceutical drugs, semiconductor designs, software algorithms (though these face additional scrutiny), industrial machinery, and chemical processes. Utility patents last for 20 years from the filing date of the patent application.

Design Patents protect the ornamental appearance of a functional item—how something looks, not how it works. The design must be:

- Novel and non-obvious

- Ornamental rather than purely functional

- Inseparable from the article it adorns

Examples include the curved shape of a Coca-Cola bottle, the distinctive pattern on the sole of Nike shoes, or the graphical user interface of a smartphone. Design patents last for 15 years from the grant date (for applications filed after May 13, 2015). They’re often used in conjunction with utility patents to provide comprehensive protection—Apple, for instance, patented both the functionality of iPhone features and the phone’s aesthetic design.

Plant Patents are the rarest type, protecting inventors who discover or develop new and distinct plant varieties through asexual reproduction (cuttings, grafting, budding—not seeds). This includes:

- Cultivated sports and mutants

- Newly found seedlings

- Hybrids created through controlled breeding

Examples include new rose varieties, novel fruit tree cultivars, or ornamental plants with unique characteristics. Plant patents last for 20 years from the filing date. Note that there’s also separate protection for sexually reproduced plants under the Plant Variety Protection Act, which is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture rather than the Patent Office.

The Patent Application Process

Obtaining a patent is far more complex and expensive than copyright or trademark protection:

1. Prior Art Search: Before filing, inventors typically conduct a search of existing patents and publications to determine if their invention is truly novel. This helps avoid wasting time and money on an application that will be rejected.

2. Preparing the Application: This includes detailed written descriptions, claims that define the scope of protection, drawings or diagrams, and an abstract. Patent applications are highly technical legal documents that typically require a patent attorney or agent to prepare properly.

3. Filing: Applications are filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) or equivalent foreign patent offices. Filing fees vary but start at several hundred dollars for small entities and can exceed thousands for larger organizations.

4. Examination: A patent examiner reviews the application, searches for prior art, and determines whether the invention meets all patentability requirements. This process typically takes 1-3 years or longer.

5. Office Actions: Examiners usually issue “office actions” rejecting or objecting to certain claims. The applicant must respond with arguments or amendments, often going through multiple rounds of back-and-forth negotiation.

6. Grant or Abandonment: If the examiner is satisfied, the patent is granted upon payment of issue fees. If not, the application may be abandoned or appealed.

Total costs for obtaining a utility patent typically range from $10,000 to $30,000 or more when including attorney fees, filing fees, and ongoing maintenance fees.

Patent Rights and Enforcement

Once granted, a patent gives the owner the exclusive right to prevent others from practicing the invention. However, patents are negative rights—they don’t grant you permission to make or sell something (that might infringe someone else’s patent), but rather the right to stop others from using your invention.

Patent owners must actively enforce their rights through:

- Cease and desist letters

- Licensing negotiations

- Litigation in federal court

Patent infringement cases are among the most expensive legal disputes, often costing millions of dollars. However, successful enforcement can result in substantial damages, including lost profits, reasonable royalties, and in cases of willful infringement, treble (triple) damages.

Maintenance and Fees

Unlike copyrights, patents require periodic maintenance fees to keep them in force:

- Utility and plant patents require fees at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after grant

- Failure to pay results in the patent expiring before its full term

- Many patents are abandoned before their full term if the technology becomes obsolete or uneconomical

International Patent Protection

Patents are territorial—a U.S. patent only protects your invention in the United States. To protect inventions internationally, inventors must file separate applications in each country or use treaties like:

- Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT): Allows filing a single international application that can be pursued in over 150 countries

- Paris Convention: Provides a priority period (12 months for utility patents) to file in other countries while maintaining your original filing date

International patent protection is extremely expensive, often costing $50,000-$100,000 or more to secure patents in multiple major markets.

Strategic Considerations

Patents involve significant strategic decisions:

- Whether to file: Patent applications require public disclosure of your invention. Sometimes trade secret protection (keeping it confidential) is more valuable, especially for processes that can’t be reverse-engineered.

- Timing: File too early and your invention might not be fully developed; file too late and you risk losing novelty or facing competition.

- Scope: Broader claims provide more protection but are harder to get granted and easier to design around. Narrower claims are more likely to be granted but provide limited protection.

- Portfolio strategy: Many companies file multiple patents covering different aspects of a single product to create a defensive patent portfolio.

The Apple Design Patent Example

Apple’s aggressive use of design patents illustrates their strategic importance. In the landmark case Apple v. Samsung, Apple successfully argued that Samsung infringed multiple design patents, including the iPhone’s rectangular shape with rounded corners, bezel, and grid of colorful icons. The case resulted in damages exceeding $1 billion (later reduced on appeal) and demonstrated that design patents can protect significant commercial value even for seemingly simple aesthetic features. This case emphasized that in consumer electronics, how a product looks can be as valuable as how it works.

Limitations and Public Policy

Not everything can be patented. Exclusions include:

- Laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas

- Mathematical formulas and algorithms (though their specific applications may be patentable)

- Literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works (these are copyrighted)

- Inventions that are illegal or contrary to public policy

- Human organisms and some genetic materials (subject to ongoing legal and ethical debate)

After a patent expires, the invention enters the public domain and anyone can freely use it. This balance between rewarding innovation and ensuring public access to knowledge is fundamental to patent policy and drives technological progress.

Key Differences at a Glance

| Aspect | Trademark | Copyright | Patent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protects | Brand names, logos, slogans | Creative works (books, art, music, code) | Inventions, processes, designs |

| Duration | renewable indefinitely | Life of author + 70 years | Utility: 20 yrs; Design: 15 yrs |

| Filed With | USPTO | U.S. Copyright Office | USPTO |

| Example | Coca-Cola logo | A novel or movie | A new pharmaceutical drug |

Why It Matters for Your Business

Many companies need more than one type of protection. For example:

-

A software company might need a patent for its algorithm, a trademark for its brand name, and copyright for its code and user manuals.

-

A restaurant might trademark its logo, copyright its menu design, and patent a unique food-prep device.

Failing to secure the right protection can leave your business exposed to copycats, lawsuits, and lost market share.

Common Questions

❓ Can I trademark an idea?

No — trademarks protect brand identifiers, not general concepts.

❓ Do I need to register a copyright?

Copyright protection exists automatically when a work is created, but registration strengthens your legal rights.

❓ Can I patent software?

Yes, but only certain types of software innovations qualify. Work with an attorney to evaluate eligibility.

Final Thoughts

Trademarks, copyrights, and patents all protect different aspects of intellectual property. The right choice depends on what you’re creating — a brand, a creative work, or a technical invention.

At Accelerate IP, we guide inventors, entrepreneurs, and small businesses through every step of the IP process. Whether you need to file a trademark, copyright, or patent, our attorneys ensure your rights are protected.

📞 Schedule a free consultation today to protect your ideas before someone else does.